Horarium Outline

monk’s day begins early in the morning, while most of the world is still

asleep. At four AM, before the sun has come up and before the birds have begun

to sing, the sound of the rising bell peals out through the dark hallways of

the monastery beckoning the sleeping monks to rise from their beds. They must

hurry after they wake up since they have to be in the church within 20 minutes

after rising for the beginning of the

Divine Office, Lauds, after which Prime and Tierce will be sung.

monk’s day begins early in the morning, while most of the world is still

asleep. At four AM, before the sun has come up and before the birds have begun

to sing, the sound of the rising bell peals out through the dark hallways of

the monastery beckoning the sleeping monks to rise from their beds. They must

hurry after they wake up since they have to be in the church within 20 minutes

after rising for the beginning of the

Divine Office, Lauds, after which Prime and Tierce will be sung.

his

morning Office is probably one of a monk’s greatest sacrifices. To wake up at

four in the morning and spend forty-five minutes chanting psalms does not come

easily to human nature. But that is the point. If it was easy and pleasant it

would not be much of a sacrifice. And so the monks can firmly hope that amidst

all their weariness and distractions their early morning prayer has done some

good for the world, that it has glorified God.

his

morning Office is probably one of a monk’s greatest sacrifices. To wake up at

four in the morning and spend forty-five minutes chanting psalms does not come

easily to human nature. But that is the point. If it was easy and pleasant it

would not be much of a sacrifice. And so the monks can firmly hope that amidst

all their weariness and distractions their early morning prayer has done some

good for the world, that it has glorified God.

hen

the morning Office is finished the monks walk back to their cells for a long

period of private prayer and spiritual reading. Often during the day, at times

like this, a monk finds himself in solitude, alone with God. Such moments are

precious to him, for it is then that he is most free to pray to his Heavenly

Father in secret and in peace.

hen

the morning Office is finished the monks walk back to their cells for a long

period of private prayer and spiritual reading. Often during the day, at times

like this, a monk finds himself in solitude, alone with God. Such moments are

precious to him, for it is then that he is most free to pray to his Heavenly

Father in secret and in peace.

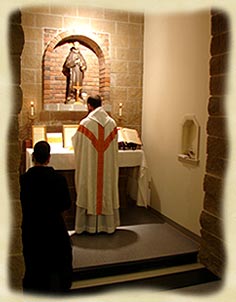

he

Conventual Mass (the Mass for the monastic community) begins at 6 o’clock.

Private Masses are also said around this time on the various side altars of the

church. This is, for a monk, the most important time of the day. For this is

when he will have the enormous privilege of offering himself, with Christ in

the unbloody reenactment of Calvary, to the Father in reparation for the sins

of mankind. And not only will he give himself to God but he himself will

receive God in Holy Communion. The opportunity to receive Communion every day

is one of the greatest blessings of religious life. Nothing on this earth could

be more sanctifying. After Mass, the community has another period for spiritual

reading and holy solitude, time to cherish the gift Christ has made of Himself

in Holy Communion.

he

Conventual Mass (the Mass for the monastic community) begins at 6 o’clock.

Private Masses are also said around this time on the various side altars of the

church. This is, for a monk, the most important time of the day. For this is

when he will have the enormous privilege of offering himself, with Christ in

the unbloody reenactment of Calvary, to the Father in reparation for the sins

of mankind. And not only will he give himself to God but he himself will

receive God in Holy Communion. The opportunity to receive Communion every day

is one of the greatest blessings of religious life. Nothing on this earth could

be more sanctifying. After Mass, the community has another period for spiritual

reading and holy solitude, time to cherish the gift Christ has made of Himself

in Holy Communion.

t

7:30 the monks gather in the refectory to eat breakfast, in silence. On most

mornings they have cereal and toast, but on fast days their morning meal

consists of bread and water, and coffee too, for those who want it. After

breakfast the grand (night) silence is broken for the day. This means that the

monks are free to speak, as necessity might require, until after Compline, when

the grand silence will again descend as a quiet and gentle blanket of peace,

enveloping the monastery in its rich folds. This night silence, as well as the

partial silence observed during the day, is not merely an empty external

silence but one which is full of God. External silence is one of the most

important ingredients for acquiring that interior quiet within the cloister of

the soul in which one can more easily hear the gentle voice of God and more

freely converse with Him by frequent heart to heart conversation, remaining in

His holy presence throughout the day.

t

7:30 the monks gather in the refectory to eat breakfast, in silence. On most

mornings they have cereal and toast, but on fast days their morning meal

consists of bread and water, and coffee too, for those who want it. After

breakfast the grand (night) silence is broken for the day. This means that the

monks are free to speak, as necessity might require, until after Compline, when

the grand silence will again descend as a quiet and gentle blanket of peace,

enveloping the monastery in its rich folds. This night silence, as well as the

partial silence observed during the day, is not merely an empty external

silence but one which is full of God. External silence is one of the most

important ingredients for acquiring that interior quiet within the cloister of

the soul in which one can more easily hear the gentle voice of God and more

freely converse with Him by frequent heart to heart conversation, remaining in

His holy presence throughout the day.

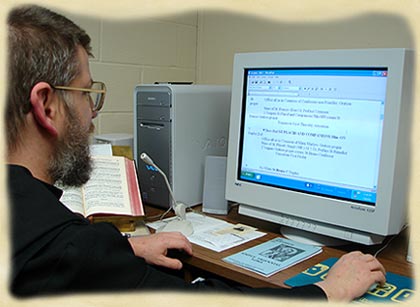

fter

breakfast they make their beds and put their cells in order and have a little

more time to read if they wish before the morning work begins. At 8:30, all the

monks head off to their various employments. Some may go out to the barn or the

greenhouse, others may have work to be done in the office or at the computer.

Working in the kitchen, cataloging books in the library, grubbing out stumps in

the forest, cleaning house; a monk finds himself doing all sorts of things. Yet

to him it is all the same. It is simply the will of God, as manifested to him

by his superiors. He will, of course, find some jobs more agreeable and

interesting than others. This is natural, since every man has his own talents

and inclinations. And it is the duty of the Abbot to try, as much as possible,

to find the right man for the job. But it often happens that the needs of the

community require a monk to sacrifice himself by embracing, wholeheartedly and

for the love of God, an employment that, naturally speaking, he would much

rather avoid. This is his offering to God and it is one of the greatest

offerings he can make.

fter

breakfast they make their beds and put their cells in order and have a little

more time to read if they wish before the morning work begins. At 8:30, all the

monks head off to their various employments. Some may go out to the barn or the

greenhouse, others may have work to be done in the office or at the computer.

Working in the kitchen, cataloging books in the library, grubbing out stumps in

the forest, cleaning house; a monk finds himself doing all sorts of things. Yet

to him it is all the same. It is simply the will of God, as manifested to him

by his superiors. He will, of course, find some jobs more agreeable and

interesting than others. This is natural, since every man has his own talents

and inclinations. And it is the duty of the Abbot to try, as much as possible,

to find the right man for the job. But it often happens that the needs of the

community require a monk to sacrifice himself by embracing, wholeheartedly and

for the love of God, an employment that, naturally speaking, he would much

rather avoid. This is his offering to God and it is one of the greatest

offerings he can make.

he

morning work period draws to a close at 11 o’clock, at which time the monks

finish what they are doing, if they can, and go back to their cells to get

cleaned up and ready for choir. The two minor Hours of Sext and None are

chanted at 11:30. Afterwards they remain in the church to spend some time with

Christ and ask themselves if they have spent the morning with Him and for His

sake. The bell rings at noon, and after they have chanted the Angelus

they process though the cloister to the refectory for dinner.

he

morning work period draws to a close at 11 o’clock, at which time the monks

finish what they are doing, if they can, and go back to their cells to get

cleaned up and ready for choir. The two minor Hours of Sext and None are

chanted at 11:30. Afterwards they remain in the church to spend some time with

Christ and ask themselves if they have spent the morning with Him and for His

sake. The bell rings at noon, and after they have chanted the Angelus

they process though the cloister to the refectory for dinner.

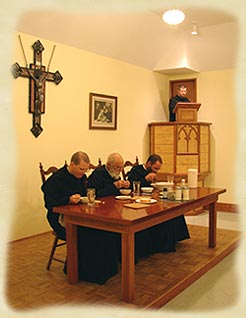

monastic refectory is a unique and sacred place. A rectangular room with a high

ceiling and two rows of plain tables along the walls, at the head of which,

under a large crucifix, is another table on a raised platform, where the Abbot,

the Prior, and the Subprior sit. To the right of this table, seeming to grow

out of the wall, is the reader’s pulpit. At the two main meals, dinner (lunch)

and supper, a monk ascends to the top of this lonely height to read to the

community while they eat. The monks are thus able to nourish both body and

soul. The food is simple but well prepared, and the meals mostly consist of

vegetables, rice, pasta, eggs, bread and more pasta. Occasionally chicken or

fish is served, but almost never the flesh of four footed animals, since St.

Benedict wanted his monks to abstain from such a luxury out of love for God. At

supper, soup is always served except on Sundays when the community eats as they

do at dinner. When the meal is over the Abbot rings a little bell and the

reader chants: Tu autem Domine miserere

nobis (But You, Lord, are merciful to us), the monks respond:

Deo gratias (Thanks be to God). Then the monks chant the prayers which

are always said before and after dinner and supper. Thus the repast ends as it

began, with the praise of God. The community processes out of the refectory

chanting Psalm 50, the Miserere, on their way back to the Church where

they will make a visit to Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. Those appointed for

the week to wash dishes stay behind to do their humble duty, as the reader eats

the food that was kept warm for him in the oven.

monastic refectory is a unique and sacred place. A rectangular room with a high

ceiling and two rows of plain tables along the walls, at the head of which,

under a large crucifix, is another table on a raised platform, where the Abbot,

the Prior, and the Subprior sit. To the right of this table, seeming to grow

out of the wall, is the reader’s pulpit. At the two main meals, dinner (lunch)

and supper, a monk ascends to the top of this lonely height to read to the

community while they eat. The monks are thus able to nourish both body and

soul. The food is simple but well prepared, and the meals mostly consist of

vegetables, rice, pasta, eggs, bread and more pasta. Occasionally chicken or

fish is served, but almost never the flesh of four footed animals, since St.

Benedict wanted his monks to abstain from such a luxury out of love for God. At

supper, soup is always served except on Sundays when the community eats as they

do at dinner. When the meal is over the Abbot rings a little bell and the

reader chants: Tu autem Domine miserere

nobis (But You, Lord, are merciful to us), the monks respond:

Deo gratias (Thanks be to God). Then the monks chant the prayers which

are always said before and after dinner and supper. Thus the repast ends as it

began, with the praise of God. The community processes out of the refectory

chanting Psalm 50, the Miserere, on their way back to the Church where

they will make a visit to Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. Those appointed for

the week to wash dishes stay behind to do their humble duty, as the reader eats

the food that was kept warm for him in the oven.

fter

the midday meal until 2:00, the monks may take a siesta. During this time they

may either sleep or read, but silence must be observed, lest the sleepy ones be

disturbed. The afternoon work period begins at 2:00, but often some of the

monks go out earlier because of the nature of their employment. In the

afternoon they work as they did in the morning, each at his assigned task. The

work permitting, they quit around 4:00 and get ready for another period of

spiritual reading that lasts until the time for Vespers at 5:15.

fter

the midday meal until 2:00, the monks may take a siesta. During this time they

may either sleep or read, but silence must be observed, lest the sleepy ones be

disturbed. The afternoon work period begins at 2:00, but often some of the

monks go out earlier because of the nature of their employment. In the

afternoon they work as they did in the morning, each at his assigned task. The

work permitting, they quit around 4:00 and get ready for another period of

spiritual reading that lasts until the time for Vespers at 5:15.

piritual

reading (Lectio Divina) is one of the

most important elements in the life of a monk (and of the laity). It is food

for the soul. Yet, like the food that nourishes the body, a monk doesn’t truly

realize the importance of his Lectio until he tries to get on without it

for a while. Then he may suffer from spiritual malnutrition. This is why

certain periods of his day are devoted to the meditative reading of spiritual

books. Holy Scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, ascetical and

mystical works and the lives of the saints make up a monk’s Lectio Divina.

But it must be much more than just reading, it must be conducive to, and

permeated with, prayer. As he reads, a monk realizes that God is speaking to

his heart by means of the words of other men, and he learns to be attentive to

His voice. His intention is not to make himself learned or to become a scholar

or satisfy curiosity but to nourish in himself the desire to belong completely

to God and to find the path that will lead most directly to Him. He knows that

it doesn’t really matter if he is not able to remember everything that he

reads. The Blessed Abbot Blosius writes, “As a vessel that often receives fresh

water remains clean, although the water that is poured in is soon poured out

again; likewise, if holy doctrine often runs through his mind, although it is

soon forgotten, it keeps his mind fresh and clean.” The monk’s reading helps

him in his struggle to cooperate with God’s grace, and as long as he keeps it

up and continues to pray and to grope after God in the darkness of faith he

will eventually be lead to that union of his soul with Christ, the Incarnate

Word, that his heart so earnestly craves.

piritual

reading (Lectio Divina) is one of the

most important elements in the life of a monk (and of the laity). It is food

for the soul. Yet, like the food that nourishes the body, a monk doesn’t truly

realize the importance of his Lectio until he tries to get on without it

for a while. Then he may suffer from spiritual malnutrition. This is why

certain periods of his day are devoted to the meditative reading of spiritual

books. Holy Scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, ascetical and

mystical works and the lives of the saints make up a monk’s Lectio Divina.

But it must be much more than just reading, it must be conducive to, and

permeated with, prayer. As he reads, a monk realizes that God is speaking to

his heart by means of the words of other men, and he learns to be attentive to

His voice. His intention is not to make himself learned or to become a scholar

or satisfy curiosity but to nourish in himself the desire to belong completely

to God and to find the path that will lead most directly to Him. He knows that

it doesn’t really matter if he is not able to remember everything that he

reads. The Blessed Abbot Blosius writes, “As a vessel that often receives fresh

water remains clean, although the water that is poured in is soon poured out

again; likewise, if holy doctrine often runs through his mind, although it is

soon forgotten, it keeps his mind fresh and clean.” The monk’s reading helps

him in his struggle to cooperate with God’s grace, and as long as he keeps it

up and continues to pray and to grope after God in the darkness of faith he

will eventually be lead to that union of his soul with Christ, the Incarnate

Word, that his heart so earnestly craves.

f

course, monks don’t read spiritual books exclusively; they read a great variety

of things outside of the times set aside for Lectio Divina. The

monastery's private library contains approximately 14,000 volumes. Those who

are studying for the priesthood have their studies in philosophy and theology.

Some monks study languages, some like to read history or biographies, and some

study birds or botany or music. One might find on the desk of a monk a book on

small engine repair between a volume of St. Augustine’s sermons and a book of

Spanish poetry. This is a good thing, because without some sort of hobby or

diversion or form of relaxation the tensions and trials of the spiritual life

would become too much of a strain.

f

course, monks don’t read spiritual books exclusively; they read a great variety

of things outside of the times set aside for Lectio Divina. The

monastery's private library contains approximately 14,000 volumes. Those who

are studying for the priesthood have their studies in philosophy and theology.

Some monks study languages, some like to read history or biographies, and some

study birds or botany or music. One might find on the desk of a monk a book on

small engine repair between a volume of St. Augustine’s sermons and a book of

Spanish poetry. This is a good thing, because without some sort of hobby or

diversion or form of relaxation the tensions and trials of the spiritual life

would become too much of a strain.

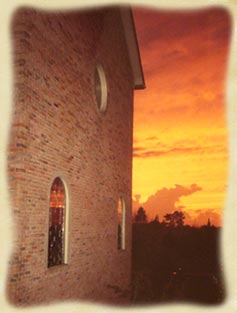

espers,

the most solemn of the hours of the Divine Office begins at 5:15 PM. By this

time the sun has begun to light the clouds on fire in its setting. All the

activities, the work and the business that the monks were engaged in during the

day have been set aside. The community gathers in the church, as they have done

so often during the day, to praise God and offer Him their hearts.

espers,

the most solemn of the hours of the Divine Office begins at 5:15 PM. By this

time the sun has begun to light the clouds on fire in its setting. All the

activities, the work and the business that the monks were engaged in during the

day have been set aside. The community gathers in the church, as they have done

so often during the day, to praise God and offer Him their hearts.

fter

Vespers the monks have a short interval before they go to the refectory for

supper at 6:00. When the community has finished eating their bowls of soup and

has made another short visit to the Blessed Sacrament, they all come together

in a special part of the monastery for an hour of community recreation. This is

a time when all the monks can relax together. They talk and laugh and play

games and even listen to a little classical music. It is a time when they can

cultivate the most precious of gifts, that joy and lightness of heart which is

so necessary in the spiritual life. After all, the angels can fly only because

they take themselves lightly. If monks did not have times when they can unwind

a little, the spiritual life could become most difficult.

fter

Vespers the monks have a short interval before they go to the refectory for

supper at 6:00. When the community has finished eating their bowls of soup and

has made another short visit to the Blessed Sacrament, they all come together

in a special part of the monastery for an hour of community recreation. This is

a time when all the monks can relax together. They talk and laugh and play

games and even listen to a little classical music. It is a time when they can

cultivate the most precious of gifts, that joy and lightness of heart which is

so necessary in the spiritual life. After all, the angels can fly only because

they take themselves lightly. If monks did not have times when they can unwind

a little, the spiritual life could become most difficult.

hen

the bell rings at 7:30 to signal the end of recreation the monks once again

make their way back to the church for Compline. As St Benedict directs in his

rule, Compline is preceded by a reading in common. For about 10 minutes the

reader for the week reads to the community from a lectern in the middle of the

choir. The readings before Compline are always spiritual in nature, whereas in

the refectory, books of a lighter nature are usually read: histories,

biographies or things of that kind.

hen

the bell rings at 7:30 to signal the end of recreation the monks once again

make their way back to the church for Compline. As St Benedict directs in his

rule, Compline is preceded by a reading in common. For about 10 minutes the

reader for the week reads to the community from a lectern in the middle of the

choir. The readings before Compline are always spiritual in nature, whereas in

the refectory, books of a lighter nature are usually read: histories,

biographies or things of that kind.

ompline,

the monastic night prayer, is unvarying throughout the year. It is a perfect

prayer for the close of day, with its unchanging psalms. The evening hymn,

Te lucis ante terminum (To Thee before the close of day), with all the

concluding prayers, expresses the same unshaken confidence in God’s loving

protection for the coming night. At the end of Compline, as the tower bell

rings, the church is in darkness except for the one light shining on the statue

of our Lady. The monks sing a last hymn to her who is the Mother of God and

their spiritual mother, as a final tribute of their filial devotion. At the

close of this Office a deepened atmosphere of peace and recollection and

silence descends upon the monastery; then follows a few minutes of silent

prayer.

ompline,

the monastic night prayer, is unvarying throughout the year. It is a perfect

prayer for the close of day, with its unchanging psalms. The evening hymn,

Te lucis ante terminum (To Thee before the close of day), with all the

concluding prayers, expresses the same unshaken confidence in God’s loving

protection for the coming night. At the end of Compline, as the tower bell

rings, the church is in darkness except for the one light shining on the statue

of our Lady. The monks sing a last hymn to her who is the Mother of God and

their spiritual mother, as a final tribute of their filial devotion. At the

close of this Office a deepened atmosphere of peace and recollection and

silence descends upon the monastery; then follows a few minutes of silent

prayer.

n

the silent darkness of the night the community then leaves the church. The

monks now have a little free time for reading or for some quiet work. They are

free to retire at any time before 9:30, when all must be in bed with lights

out.

n

the silent darkness of the night the community then leaves the church. The

monks now have a little free time for reading or for some quiet work. They are

free to retire at any time before 9:30, when all must be in bed with lights

out.